Canadians know oil and the controversy that follows it as well as they know hockey and poutine.

And now that Neil Young’s cross-country tour is supporting a First Nation’s lawsuit against Shell, the flames are being fanned once again. Yet, what many Canadians may not know is that for more than 20 years, indigenous communities in Ecuador’s Amazon have been bogged down in an eerily similar battle against Chevron Corporation.

It’s a battle over what’s been described as the largest oil-related environmental catastrophe in history.

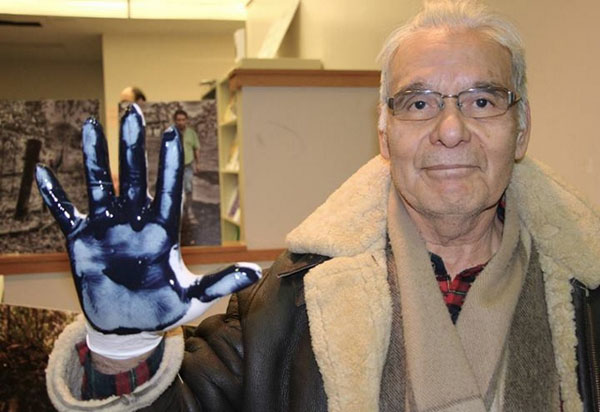

Photo courtesy of the Committee in Solidarity with the Indigenous People of Ecuador Affected by Chevron

But that’s about to change now that the case has landed in the Ontario judicial system, a turn of events that’s rallying the Canadian-Ecuadorian community. The Committee in Solidarity with the Indigenous People of Ecuador Affected by Chevron is a new grassroots group organizing workshops throughout the country to raise awareness about the case and to recruit potential demonstrators.

“We are people involved in social and environmental justice,” said Santiago Escobar, a whistleblower who in 2009 became an instrumental party in the case against Chevron. “And we are in the process of building a strong network throughout Canada.”

In 2011, the 30,000 plaintiffs from indigenous and farming communities received a $9.5 billion judgment against Chevron in Ecuador’s courts. When Chevron refused to abide by that judgment, it pulled its assets from the country quickly. So the plaintiffs exercised their legal right to pursue the matter in another court outside of Ecuador. They are now seeking enforcement of that judgment in Canada, Brazil and Argentina, and the workshops are meant to pressure the oil giant to pay its debt.

Earlier this month, York University’s Glendon Campus hosted one of these workshops, which was sponsored by Ecuador’s Embassy in Ottawa, Ecuador’s Consulate in Toronto and the Association of Ecuadorians in Ontario. Also at the event were representatives from Toronto-based consulates from Spain, France, Cuba and Mexico, as well as Toronto’s Ward 17 councillor.

“As a citizen of the world, not only as city councillor, my obligation is to stand up when I see that something needs to be done,” said Cesar Palacio, who represents the Davenport-St. Clair-Dufferin region, in a telephone interview. “And (in this case), it’s crystal clear that there were wrongs that must be corrected.”

In 2011, Chevron was found guilty of dumping billions of gallons of toxic waste and abandoning more than 900 opened toxic waste pits in Ecuador’s Lago Agrio region in the Amazon. Since then, Chevron has countersued the plaintiffs’ lawyers and consultants in the United States arguing that they won the case through fraud. Ecuador’s Ambassador to Canada, Andres Teran-Parral, believes that Chevron is simply arguing whatever its $450-million-a-year legal team can muster in a desperate attempt to besmirch the Ecuadorean government.

“We are promoting the case because we saw Chevron is running a smear campaign against Ecuador,” he said in an interview as he pointed out that Chevron’s also suing Ecuador’s government in a UN tribunal in The Hague for alleged corruption and manipulation of the justice system. “And we would like to let people know the big picture – what happened in the past and what is going on right now.”

The Committee in Solidarity has also launched a Facebook campaign, titled Chevron’s Dirty Hand, which uses guerrilla-marketing techniques to inundate social media news-feeds with articles, videos, testaments and petitions from all over the world demanding the corporation pay what it owes. Actors Danny Glover and Mia Farrow, and Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters are some of the celebrities who’ve shown support for the affected communities. Seeing the effect Neil Young’s support for the First Nation’s lawsuit is having in Canada, the committee hopes to establish contact directly with these celebrities to draw a bigger audience.

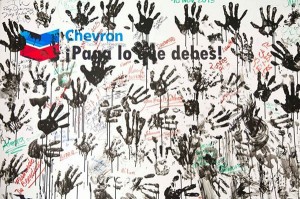

Photo courtesy of the Committee in Solidarity with the Indigenous People of Ecuador Affected by Chevron

The campaign also features original content such as videos of citizens, environmental activists and indigenous groups like the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation—in Brantford—expressing their solidarity by covering a cloth showing the Chevron logo with oil-soaked handprints.

“We are also in contact with the Unist’ot’en (Camp) who are battling against Chevron and other companies in resistance to the Pacific Trails Pipeline in Northern B.C.,” said Escobar. “We think that indigenous peoples from Canada and Ecuador have similar problems…such as corporations that put profit first over common good and we think that affected communities can learn and support each other beyond borders.”

The committee is planning to stage more events throughout Toronto, including possible marches outside the courtroom hearing the case.

“With the lawsuit now being fought in Canadian courts, the Canadian public seems to be very interested in learning more,” said Escobar. “If the communities prevail on their enforcement action, this would open the door to make corporations accountable all over the world…which is why the awareness and solidarity of Canadians is of the utmost importance at this stage of the struggle.”