In the 10 years he’s been an officer of the Ontario Provincial Police, Hesham El Sayed has never had to fire his gun.

“The job’s not for everyone, that’s for sure. It never gets easy. You should go to every call scared, that’s what I think.”

El Sayed, 35 and a London resident, has been in many situations that could have easily escalated to levels of danger and violence. He says while every situation is different, his reaction when he gets the call is always the same.

“Your heart’s racing a mile a minute. There’s so much happening all at once, and I always just have to stop and think, you know, at the end of the day, I have to get home to my family. I have to get home to my kids. But at the same time, you’ve got to think of the person calling, their life and their family as well.”

In light of the recent non-indictment of Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, the death of Eric Garner where the New York City police officers were also allowed to walk free, or the shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, the public seems to be paying more attention to how police officers behave in any incident.

But living in a social media age opens police up to scrutiny from the public they have never faced before. All citizens with a computer now have the ability to criticize the actions of their local police force, though they may not have even the slightest knowledge of police procedure nor how potentially violent situations should be handled.

I certainly had no idea under what circumstances it was legally acceptable for a police officer to fire his gun.

And while much of the current scrutiny is on American police, Canadians may also be feeling some of that tension too.

The shooting of Sammy Yatim in a Toronto streetcar almost two years ago – an incident videotaped and viewed by millions – echoed some of the incidents of our neighbors to the south.

Officer El Sayed discussed these high-profile American cases with patience and sympathy.

“I understand how different it is in the States, and you can scratch your head and ask why that happened every time. But as an officer, obviously I sympathize. You have to think of yourself, your partner and the public. That’s how it is.”

Because of the role social media plays in our day-to-day lives, El Sayed says there is now more emphasis on accountability in their training as enforcers of the law.

“Everyone’s got a cellphone and a camera, so it’s constantly being said, ‘you’re being watched.’ You’re in a position of authority; you don’t want to abuse it. You could lose the job you love in an instant and that’s not a risk I’m willing to take.”

Cellphone footage and viral videos allow the untrained public to pass judgement on the actions of police officers, no matter the circumstances. El Sayed says this was a crucial point in the year-long process necessary to become an officer.

“It’s a very long and detail-oriented process,” he says. “From the day I applied to the day I got the job it was about a year, a year and a half. But it makes sense. You’re putting these guys in a uniform and they’re making decisions for people. That’s important.”

Sergeant Cheryl Armstrong, a community services officer with the London Police Services, says it’s difficult to truly judge the actions of another officer because so much of what’s happening is analyzed and understood through the perception of the dispatched officer.

“Every officer’s perception is obviously different,” she says. “So if an officer of smaller stature is up against an individual with a larger build, the threat can seem more urgent. And then add a weapon to the situation, if the individual has the skills to use it against the officers present … all that is take into account.”

“But when things are chaotic, the officers rely on training and communication,” Armstrong says. “Communication is always key.”

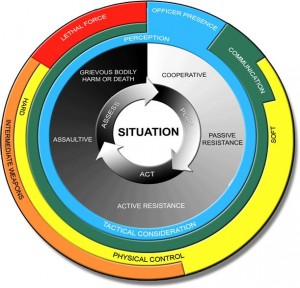

Communication is a crucial part of the National Use of Force Framework, the model used by the London Police serves and the Ontario Provincial Police. And at its core are three words the officers on both forces use repeatedly: assess, plan, act.

El Sayed is a firm believer in the power of communication. He tells the story of a domestic situation that he was called to check out, which was handled by “getting hands on” and handcuffing the individual. But on the drive away from the scene, the man started behaving violently.

Instead of approaching the situation aggressively, El Sayed noticed the man’s Maple Leaf’s hat and started discussing that season’s statistics. “We talked about hockey for about an hour. I kind of developed a rapport with him,” says El Sayed with a laugh. “In instances like that, using communication is just better for everybody.”

These kinds of scenarios are more common than assumed, far more common than the incidents that end in violence or aggression. An officer with London Police Services, who has asked to remain anonymous, had a similar story to share.

He faced a situation where a young woman had a knife to her own throat. She was threatening to harm herself and in a matter of seconds she could also have harmed someone else. The situation was tense and had to be diffused in a tactical manner, he said. And while it would have been easy to approach the situation in a panic, the officers remained calm and managed to get control by simply asking her what the problem was. It sounds almost too simple to be true, but that was all it took.

“I actually listened to what she had to say and she dropped the knife. She didn’t harm herself,” the officer said.

“It’s so difficult because you have only a few seconds to determine so many things about the person: are they suffering from a mental illness, do they have a medical condition, what kind of aggravating factors do their lives contribute – you don’t have all the facts. You have to act on what’s in front of you, which sometimes is just they have a weapon and they shouldn’t.”

El Sayed shared a similar sentiment, saying that much of their training is useless without an ability to assess the situation at hand. And that includes knowing when to use lethal force.

So, when is it legally acceptable for an officer to use his weapon? El Sayed and other officers interviewed said you can draw your weapon if you see someone with anything that can harm you or the public. What happens after that is evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

“Until he’s handcuffed, I can’t put my firearm back in the holster,” he says. “What the public needs to understand is that, if an individual appears to have a weapon, we have to assume that he’s going to use lethal force against us. That’s the hard thing about our jobs.”

A police training session by Youtube trainer Samir Seif