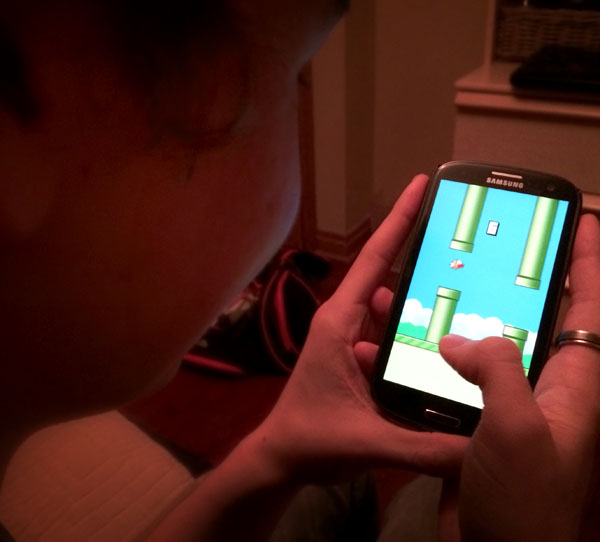

The tense silence of Jordan Furlong playing a game on his cellphone is abruptly broken by a loud, frustrated string of cursing, and a mock motion of throwing his phone to the floor.

And then he starts over and repeats.

The mobile game Flappy Bird is on the other side of his phone screen. And it’s aggravating Furlong, 17, to a point where the bursts of swear words turn into deep inhales of breath and quietly shaking his head in disbelief.

“I want to get past 50, and then I’m deleting it,” he said, referring to the levels in the game. “I can’t get past 48 – it’s really annoying.”

Flappy Bird is the latest obsession in mobile games. It’s simply designed and consists of the player tapping the screen to make a bird fly and navigate through narrow pipes. If the bird falls, you go straight back to the beginning.

“I guess it’s something that’s so insignificant and it seems so easy,” Furlong said. “I’m just angry at myself that it’s beating me.”

Some may have experienced a similar feeling when playing a video game on their cellphone, computer or television. Others, like me, have very little patience for such things, and tend to be baffled by the persistence of some gamers.

We know there is such thing as video game addiction – we saw this especially with World of Warcraft (a massive online, role-playing game), where some gamers were subject to interventions.

“I made myself stop because I couldn’t do both school and World of Warcraft,” said Furlong, a gamer from Milton, Ont.

Even a simple game like Flappy Bird got so addictive that the creator Don Nguyen took it down from the App Store.

He told Forbes magazine he designed the game to play for a few minutes when someone is relaxed. “But it happened to become an addictive product,” Nguyen said. “I think it has become a problem.”

So what is it about these games that keep gamers glued to their devices?

John Hopson, the head of User Research at Bungie – the game developer that made Halo – wrote an article for Gamasutra that sheds some light on this question.

Hopson, who has a PhD in behavioural and brain sciences, explained there are techniques used in game design that mirror observations found in behavioural psychology experiments.

Specifically, experiments done by psychologist B.F. Skinner, who provided food pellets to rats depending on how often they pressed on a lever.

For example, the rat would sometimes have to press the lever 10 times before receiving a food pellet, and would do so without fail. Basically, it’s a task and reward system. In games, a player moves up a level by having to kill a certain number of opponents.

like “Sweet” and “Divine.”

Photo by Karmen Wells

“There are actions on the part of the participant which provide a reward under specific circumstances,” wrote Hopson. “This is not to say that players are the same as rats, but that there are general rules of learning which apply equally to both.”

To make it more complicated, rewards can be given at random intervals as long as the player keeps playing. This becomes addicting because of the mentality that the next task may be the one to get them the reward, Hopson said.

Think of it like a slot machine – people throwing in coin after coin, thinking each pull of the lever could be the one to win them the jackpot.

This is one of Hopson’s concluding “recipes” for how to make a player maintain a high and consistent rate of activity.

Dr. Kevin Harrigan, the lead researcher for Problem Gambling at the University of Waterloo, said slot machines provide small rewards and big rewards, and the reaction from the player is the same for both.

“Many of the rewards (on a slot machine) are actually less than the player wagers, but the machine celebrates it the same way as a big win,” Harrigan explained in an interview. “And we’ve measured their sweat while they play … and for every time they get one of these big wins they get a similar reaction physiologically as with a small, or actually negative reward.”

You can see this type of reward system in the Candy Crush Saga, where a player is encouraged with the little tasks they’ve completed.

“It raises a concern that people who play these machines, while they’re losing money, they’re underlining system is treating it as if they’re good things,” Harrigan said.

Hopson also provided a recipe to “keep players playing forever.” To keep a player’s momentum, Hopson suggested an “avoidance schedule, where the players work to prevent bad things from happening.”

You can see this technique in the mobile game FarmVille – if a player doesn’t attend to their crops on a regular basis, the crops will shrivel up and die, turning all their hard work into pixel dust.

But what’s really so bad about developers wanting to create successful games and players wanting to play them? And does that change when money’s involved?

Nowadays many games on the App Store fall under the freemium, or free-to-play, category. These are games that you pay nothing to install, but can later be charged for premiums like advanced features, virtual goods and more.

Take Candy Crush, for example. It’s free to download, but once you get higher in levels, the harder the game gets, and that’s when they start prompting you to buy quick advances, like the lollipop hammer for 99 cents.

Photo by Karmen Wells

Damir Slogar, CEO and founder of mobile game developer Big Blue Bubble in London, explained the free-to-play model was caused by a race to the bottom when small budget developers started lowering the cost of their games.

It was the market’s answer to desperate developers wanting to make money, he said, because players were expecting half a million dollar games for only 99 cents.

But when you combine the addictive quality of a game with in-app purchases, you start to see a potential problem.

Candy Crush uses a common levelling up system where it’s easy to complete the first levels – getting you hooked – then it becomes more difficult as the game goes on (even too difficult for a computer, according to an Australian computer scientist in the gaming blog Kotaku), unless you buy the boosters.

Slogar said Candy Crush is a perfect example of how the free-to-play market works. “Anyone who wants to play game for free can. It’s obviously up to you how far you want to go in the game or not,” he explained. “I can’t say whether this is super positive or super negative. It just works, right?”

It definitely works for Candy Crush, which just dropped from the first to second top grossing app – raking in over $1 million a day from in-app purchases alone.

Furlong, who used to play Candy Crush, can relate to the cost of freemium games, and he said the mobile game DragonVale is even worse.

“You want every dragon, but to do that it’s so impossibly hard,” he explained. “And they make you wait like 46 hours just to get shut down and not get it.” Afterwards, they let you know you can improve your chances if you pay up for more gems to try again – some purchases can be up to $100, Furlong said.

“I don’t think it’s fair.”

Some games place a reward just out of reach, which then leads to players throwing down cash to keep going.

Jonathan Blow, an award-winning game developer, said at the 2007 Free Play conference in Australia, that players would usually avoid boring tasks and games.

But developers found a way around this “by plugging into their pleasure centres and giving them scheduled rewards and we convince them to pay us money and waste their lives in front of our game in this exploitative fashion,” he said.

Slogar disagrees. “I don’t see the game being more addictive than anything else. You can say you’re addicted to pizza or something … even though it’s not good for you. Same thing for the game; after a certain limit you shouldn’t spend more money.”

Slogar also said he doesn’t see the difference between buying a $60 game for your console – like an XBox or Playstation – that you may not finish, and paying your way to finish a freemium game.

“If you’re playing a single-player game then I don’t have any problem in paying to move further in the game,” he said. “It would be totally different if you were playing against someone else.”

Deleting Flappy Bird probably didn’t shake up the free-to-play market too much, but it was an unusual move by the creator. Although Nguyen’s reportedly making over $50,000 a day, it’s through advertisements, not freemiums. He cancelled it because of how addictive it became.

Free-to-play is still new in the market, but whether it sees the errors of its ways or not, Slogar said it’s here to stay, and in the end it’s up to the player.

“I’m usually a good judge,” Furlong said, “so if they impact me too much and I end up spending too much money, then I don’t think it’s worth it in the end.”