Kate Upton is no stranger to celebrity endorsements, but during this year’s Super Bowl, her, uhh, “acting talents” were on full display, hawking something completely different – free video games.

Game of War commercial featuring Kate Upton.

She wasn’t alone. While Upton starred in a Game of War commercial, Liam Neeson promoted Clash of Clans. Both ads boasted that the mobile games were free to play. But just how could free games afford to spend so much on advertising during the most-watched television event of the year? I decided to download the games and find out for myself.

Clash of Clans commercial with a late cameo by Liam Neeson.

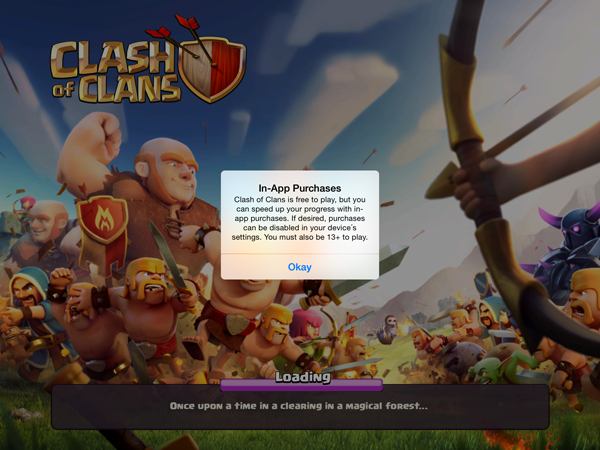

A minute into Clash of Clans and Game of War and it’s clear where these games are making money. Disclaimers before the games even load say it’s “free to play, but you can speed up your progress with in-app purchases.”

I didn’t understand why a player would want to “speed up” progress until I started playing. The games are similar in design – players build up a society by arranging and upgrading buildings, then forming alliances with other players. There’s no endpoint in either game, just endless upgrading to have a better society than your competitors. And all of this takes a lot of time.

The first batch of upgrades takes seconds. The next, minutes. Now a week in, my upgrades take days, and it’s only getting worse. As I progress, there are fewer things I can actually build or upgrade unless I want to start spending money. Real cash goes towards shortcutting these upgrades or getting exclusive content.

And while I didn’t drop any money in my first week playing, my alliance member “Busta Blahout” has. “Busta,” whose real name is Zac Blahout, says he’s spent over $40 on these games.

“I just didn’t have the patience,” said Blahout, a 22-year-old Ottawa University student. “You begin to base your life around the time schedules in the game. If my (virtual) town needs an upgrade, I’ve got to wait days. If I need (virtual) cash for those upgrades, I’ve got to log in to the game way too frequently. Eventually I just caved and threw in some real money.”

Blahout built up his Clash of Clans village much quicker with the real money he spent. This is known in the gaming community as “pay-to-win” microtransactions. Blahout says spending money on pay-to-wins is unrewarding.

“There’s a sense of regret almost instantly after paying,” he said. “You’re questioning why you spent money on something that seems so valueless, and even though it gives you an instant boost, it’s not long before you’re back on the game’s schedule and looking to pay (real) money again.”

Blahout’s virtual town is a continent compared to mine, which suggested real money is the best way to advance in Clans. But I made it through my first week without having spent a cent.

In fact, most people I talked to about the game said they have never put money into the game. But if so few people are spending cash in Clash of Clans or Game of War, how can the developers stay in business, let alone pay for Super Bowl commercials?

Quite easily, says Western University professor Michael Katchabaw, who teaches game development and design. Even though few people are paying money within the game, it still adds up.

Photo courtesy of Mike Katchabaw

“If you have a game that costs 99 cents to install, you might have 10,000 people buy it and that’s it,” Katchabaw says. “But if you take a look at a game like Clash of Clans where you have millions or tens of millions playing it, and only three to five percent actually periodically making purchases of 99 cents, you’re looking at a lot more money.”

And Clans’ developer, Supercell, is making a lot of money. In 2013, the small Finnish studio took in $829 million, according to Forbes.

It’s not just Supercell using this model. A recent report on The Verge says in-app purchases account for 98 per cent of worldwide revenue in Google’s mobile application store. Most of those purchases are for games like Clash of Clans, and the most money spent comes from Japan, followed by the United States.

Katchabaw says developers base this model on psychology and entertainment value. Users compare the gaming experience to other entertainment options, like going to the movies.

“Users say, ‘I’m playing this game and I’m putting a lot more time into this game than just two hours worth. It’s actually psychologically easier for them to spend two dollars on (the game) because they’re getting great entertainment value for their dollar.”

And the strategy is starting to seep into more traditional videogames for Xbox and PlayStation. The most recent iterations of popular games like Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto feature pay-to-win options, even though the games themselves can cost as much as $70.

It’s great for developers who are finding more ways to monetize the gaming experience, says Katchabaw, but there’s a major issue with the pay-to-win option.

“Being able to ‘pay to win’ disrupts the natural balance and fairness of a game,” he said. “Especially if the game has a multiplayer element to it. If it’s entirely a single player game, it’s less of an issue. If you choose to buy your way to the top to accelerate your progress, then your choice only impacts you.”

Katchabaw’s not the only one dismayed by the pay-to-win model. User backlash against these games led to Apple recently creating a new App Store category called “Pay Once and Play.” The category promotes games that cost money to download, but don’t have any pay-to-win options.

I’ve been sucked into these pay-to-win games for two weeks now, and even with my constant attention, I’m still at a serious disadvantage. I tried buying my way to the top in the last few days, hoping to level the playing field with people like Blahout. My $10 went towards some town upgrades, but soon that money was gone and I was back playing the waiting game.

Now I’m stuck, muttering at my phone like Liam Neeson.